by Oppositional Conversations Editorial Board

Focusing on “Identifications” fascinates us because it centers us inside a slippage in meaning first identified by W.E.B Du Bois in 1940. This is the slippage between “identity”—loosely, who you believe you are in the context of the groups with whom you choose to affiliate—and identification—an assignment to a group outside your control and imposed by a more powerful entity such as the state.

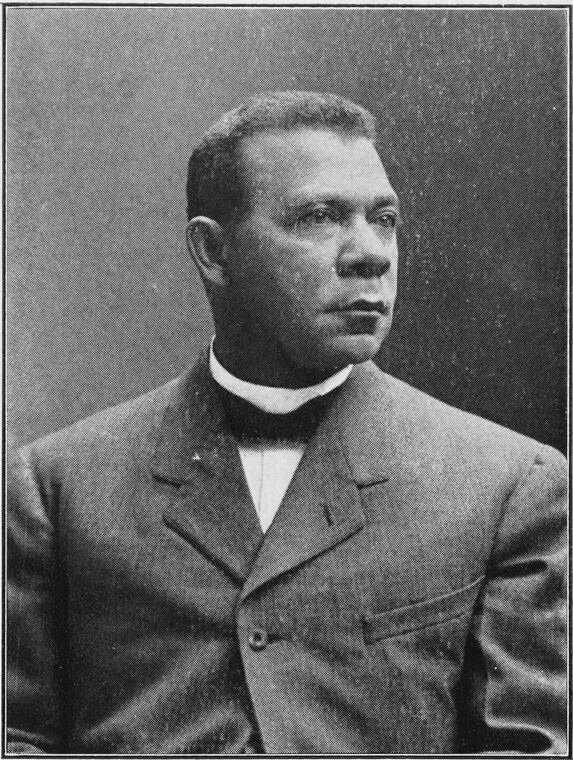

Du Bois wrote his first essays in 1896 for the African Civilization Society which was run by Alexander Crummell. He called one of those essays “Of Our Spiritual Strivings.” In it Du Bois struggled to identify what made persons of African descent a “united group.” Borrowing from Hegel he determined that each national grouping had a distinct “spirit.” Hence the origins of the idea of “soul” in his The Souls of Black Folk, published in 1903. Just shy of four decades later Du Bois changed his view. In his autobiography, Dusk of Dawn, he reflected that he had spent a good chunk of his life trying to ascertain what gave Black people a “group” or corporate identity. He averred that, after four decades of looking for that “geist”/spirit, culture, or mystical substance, his searches had come up empty. A Black man, he concluded, was someone who “must ride Jim Crow in Georgia.” In other words, Black identity inextricably involves a kind of violence in which one does not get to decide whether one belongs to (dare we say “identifies with”) a particular group. This particular group is one to which one is forcibly assigned—by the train conductor, the Jim Crow Laws, or the child on the train pointing at Frantz Fanon and saying, “Look Mama, a Negro!”

We note a third aspect of “identification” that has emerged since DuBois died in 1963: the dynamic of negotiating the incommensurable contingencies set in motion whenever we say something like, “Who do you identify with?” An almost random example helps get at what we mean.

Late in July 2020, Joy-Ann Reid took over the 7:00 pm news-hour, which had been left vacant, with her own show on MSNBC. Her new show, The ReidOut, was hailed as a “victory for Black women.” We were told (again and again) that Joy’s victory was our victory. And if we (by this “we” we mean “Black women”) didn’t arrive at that conclusion on our own…well, there were millions of people right there ready to remind us of this fact. “So happy that my 10-year-old daughter can turn on TV and see someone who looks like her,” tweeted @ProudDad. If that wasn’t enough, Tiffany Cross (who inherited Joy’s abandoned weekend show) squealed with glee that “this is a victory for all of us ya’ll.” It certainly was a victory for Tiffany. She got her own show after all. Absent a very peculiar notion of “group identification” however we struggle to see how it is a victory for us. No one expects middle-class White guys to be satisfied with: “Jeff Bezos is set to become a trillionaire in 2026, so that is a victory for ME!”